Peter Milton’s TSUNAMI: Turner, Constable, & Ruskin at Sea in a New American Print

James A. W. Heffernan

A few years ago, Tate Britain mounted the kind of exhibition that would have thrilled the contentious heart of J.M.W.Turner. Taking their cue from the terms of Turner’s well-known bequest, which left two of his paintings to the National Gallery on condition that they be “placed by the side of” two paintings by Claude Lorraine, the organizers of Turner & the Masters (23 September 2009-31 January 2010) hung several dozen of his paintings beside the works of Rembrandt, Rubens, Poussin, Titian, and Canaletto.[1] Besides Claude, these were the masters that Turner had set out to emulate: to absorb, reflect, and re-create in his own inimitable way.

Turner was equally contentious with his own contemporaries. During his legendary performances on varnishing days at the Royal Academy, when he would labor from dawn to dark in full view of other artists, he aimed to show that he could “outwork and kill” every one of them.[2] After the young David Wilkie won acclaim with a painting called The Village Politicians in 1806, the first year he exhibited at the Royal Academy, Turner painted for the next year’s exhibition a genre piece of his own--A Country Blacksmith Disputing upon the Price of Iron. Hung beside Wilkie’s Blind Fiddler, the “overpowering brightness” of A Country Blacksmith is said to have eclipsed Wilkie’s Fiddler, and since Turner also exhibited Sun Rising Through Vapour in 1807, the two paintings together reportedly ‘“killed” every picture within range of their effects.’[3]

John Constable, Opening of Waterloo Bridge, ex. 1832

J.M.W. Turner, Helvoetsluys, ex. 1832

Turner did this sort of thing throughout his career. In the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1832, Constable’s magnificent Opening of Waterloo Bridge was hung beside Turner’s Helvoetsluys , a grey-blue, serenely Ruysdaelian painting of sails in a Dutch harbor. A few days before the opening, after noticing Constable “heightening” the barges in his painting “with vermilion and lake,” Turner added “a round daub of red lead . . . on his grey sea” and went off without a word. Seeing that the intensity of Turner’s red (barely reproduced here on the buoy at lower right) not only stood out against the coolness of his sea-piece but also made even Constable’s colors “look weak,” Constable told C.R. Leslie that Turner had thus “fired a gun.”[4]

He aimed his pictorial guns not only at the artists of his own time but also at some of his precursors. Writing to a print-publisher in 1822, Turner proposed that a set of engravings be made from his own works to compete with the set that William Woollett had some years earlier made from four historical landscapes by Richard Wilson. Eager to show that he could “contend with such powerful antagonists as Wilson and Woollett,” Turner declares: “to succeed would perhaps form another epoch in the English school; and, if we fall, we fall by contending with giant strength.”[5] The giant strength with which Turner spent most of his professional life contending, however, belonged not to Wilson but to Claude. After seeing Claude’s Sacrifice to Apollo for the first time in 1799, when he was 23, Turner reportedly said that “he was both pleased and unhappy while he viewed it, it seemed to be beyond the power of imitation.”[6] Yet for the rest of his life Turner repeatedly aimed to show that he could match Claude’s achievement. Long before stipulating that the National Gallery hang two of his paintings beside a pair of Claude’s, the seventy engravings he commissioned and published in periodical sets from 1807 to 1819 under the title of Liber Studiorum were meant to exhibit a variety of “Landscape Compositions” equal in power to the sketches of Claude’s Liber Studiorum--a graphic record of all Claude’s works that had been engraved by Richard Earlom two years after Turner’s birth and that appeared, like Turner’s Liber, right up to 1819.[7] Turner thus sought to show that he could stand—and withstand--comparison with one of the greatest of his European precursors.

J.M.W. Turner, Bridge of Sighs: Ducal Palace and Custom House, Venice: Canaletti [sic] Painting, by J.M.W. Turner. 1833. Oil on canvas 51.1 × 81.6 cm. (Tate Britain, London).

The wittiest demonstration of this point is a painting first exhibited in 1833 and ostensibly showing Canaletto at work: Bridge of Sighs: Ducal Palace and Custom House, Venice: Canaletti [sic] Painting (left). With a single gondola at right, a cluster of barges at left, and the specified buildings in the middle distance,it puts Caneletto and his easel in the lower left corner—as shown in the detail to the left.

Canaletto, Entrance to the Grand Canal, Venice. c. 1730

But unlike the watery city depicted here, Canaletto’s paintings of Venice are insistently linear. Largely ignoring reflections in water, he makes his buildings form a solid barrier between the water and the sky. By contrast, Turner uses watery reflections to suppress the contrast between solid and liquid as well as the line between water and sky, and thus to literalize the metaphor that art reflects nature—or in this case, architecture. Consequently, Turner’s Canaletto is painting a Venice that has already become a painting by Turner.

I have recapitulated these well-known points about Turner’s contentiousness—including his contentious use of prints—as a way of introducing a recent print showing Turner himself at work in the midst of a tsunami. It exemplifies the recent work of Peter Milton, who—after etching prints for more than fifty years—has recently been producing them by means of digital technology.[8] But for Milton, this turn to the digital is really just a delicate new bend. Digital technology allows him to do more easily what he had been doing for more than thirty years before turning to the mouse: assembling, transforming, and synthesizing individual pictures—many of them photographs--by means of collage, which is the constant factor in virtually all of his work (See Heffernan, “Peter Milton’s Turn”). Strictly speaking, a collage is a work of art assembled not from hand-drawn figures but from pre-existing objects--such as photographs and news clippings--that are pasted onto a flat surface (the French word coller means “to paste or glue”). Paste is not essential to collage, but arrangement is. In the early twentieth century, when collage became a serious form of art, some of its practitioners frankly dismissed the value of draughtsmanship. Marcel Duchamp, for one, announced that his collages reflected “the choice of the mind, not . . . the ability or cleverness of the hand . . . ”[9] Besides privileging the mind over the hand, most collages are spatially incoherent, simply juxtaposing one visible artifact—such as a text or photograph-- with another such artifact on a two-dimensional plane.

Milton’s prints are radically different. While often assembled from the juxtaposition of individual pictures and photographs that are now digitally integrated, they are both spatially coherent and meticulously drawn. Their composition ultimately depends on Milton’s draughtsmanship, which erases every trace of mere juxtaposition. This new print is no exception. “Though originally derived from found photographic source material,” Milton writes, “everything becomes layered, fused, transformed, thrown out, redrawn....the primacy of touch is everywhere.” [10] This primacy of touch is now more visible than ever in the light box editions of his prints (See Johnson on Light Boxes), which display his magisterial draughtsmanship with breathtaking radiance.

Mary Cassat, Girl Arranging Her Hair (1886)

Peter Milton, Mary's Turn Detail Image

The content of Milton’s work is as remarkable as its style. For many years, he has been re-creating elaborately furnished, architecturally intricate settings drawn from the nineteenth and earlier twentieth century and populating them with figures taken from literature and art. In Mary’s Turn (1994), for instance, Mary Cassatt takes her turn at the billiard table while observed by Edgar Degas as well as by various figures drawn from Mary’s paintings, including a re-arranged version of Cassatt’s Girl Arranging her Hair (1886). Not incidentally, Mary’s Turn was prompted by a story of contention. When Degas implicitly questioned Cassatt’s right to judge the style of a male artist, she “took offense” and produced the painting just mentioned, whereupon Degas himself exclaimed, “What drawing! What style!”[11]

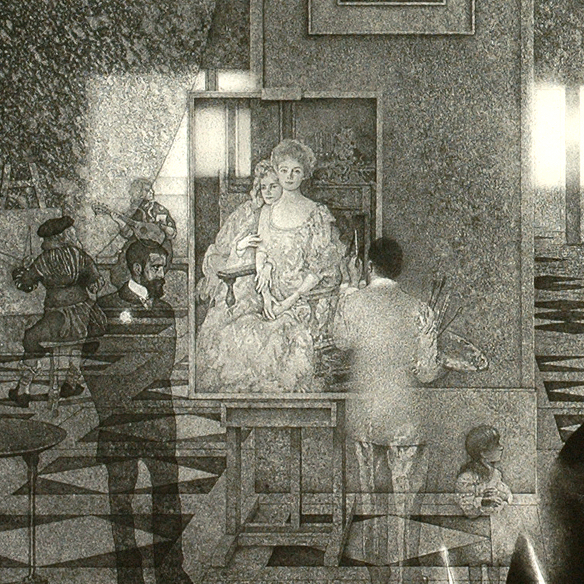

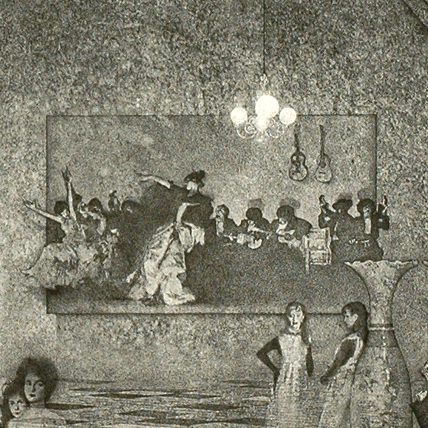

Since Mary’s Turn, Milton’s prints have featured several other artists at work and sometimes writers as well. In Search of Lost Time (2006), for instance, richly evokes not only Marcel Proust but also various artists and their works. In the detail at left above, the figure of Jan Vermeer taken from his own Allegory of Painting (left below) sits working on a canvas at extreme left while a doubly portrayed John Singer Sargent watches himself painting a double portrait: Mrs Fiske Warren and Her Daughter Rachel (left of center below). In the center of the print, as shown in the detail above right, a large, columned hall is populated by girls drawn from Sargent’s Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (right of center below) and hung with several of his other paintings, including a reversed version of El Jaleo (below right).

Johannes Vermeer, Allegory of Painting (ca. 1666)

John Singer Sargent, Mrs. Fiske Warren & Her Daughter Rachel (1903)

John Singer Sargent, Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882)

John Singer Sargent, El Jaleo (1882)

Milton’s work has long been inspired by literature as well as art. Almost fifty years ago, he re-created a short story by Henry James, “The Jolly Corner,” in a remarkable portfolio of 21 prints. In the early 1990s he produced another set of prints based on James’s novella, The Aspern Papers, and in Hide and Seek (2014), which takes its name from a painting by William Merritt Chase, the novelist himself is portrayed as a painter. As Chase stands by his painting with brush in hand (below left detail), he watches James illustrate his own novella, Turn of the Screw, with a child’s wide-eyed face: a close-up that encapsulates the story of children terrified by would-be ghosts. Elsewhere in the print (below right detail), Sargent’s Daughters is re-constructed with the ghostly figure of Sargent himself in the right foreground, and some of the girls from this painting as well as from Chase’s have slipped out of their frames to run across the floor.

Peter Milton, Tsunami (2015)

In turning from painters such as Cassatt, Chase, and Sargent to the depiction of Turner in Tsunami, Milton also turns from serene interiors to the sea—Turner’s favorite subject-- at its most turbulent. Like Mary’s Turn, Tsunami was prompted by a story: in this case a story originating from John Ruskin’s report of what Turner said to a clergyman about the genesis of his Snow Storm (left below)..

J.M.W. Turner, Snow Storm: Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth, ex. 1842

Horace Vernet, Joseph Vernet Attached to the Mast Studying the Effects of the Storm (1822)

“I got the sailors to lash me to the mast to observe [the storm]; I was lashed for four hours, and I did not expect to escape, but I felt bound to record it if I did.”[12] In doing so, he not only impersonated Ulysses, as critics have often noted, but also re-enacted the celebrated feat of Claude-Joseph Vernet, the eighteenth-century French seascape painter whose work Turner knew very well[13] and whose feat was depicted in 1822 by his grandson Horace (right above).

Whether or not Turner knew Vernet’s picture firsthand, we can profitably study it as a precursor to Snow Storm, precisely because Turner’s picture is so different. In Horace Vernet’s painting of his grandfather on a stormy sea, the artist is commandingly poised. Disturbed by neither the dramatically steep diagonal of the hull nor the slant of lightning at upper right, he stands boldly upright at the intersection of the one nearly vertical mast and the perfectly level horizon behind him. The stability of the artist in the picture corresponds to the stability of the artist who painted it. He carefully preserves his own vantage point from the upheaval that he tries to represent.

In Turner’s picture, all traditional bases of visual stability slide away. The horizon itself tilts, and instead of a vertical line in the center we find a bowed and slanted mast. The bent mast signifies Turner’s struggle to find a form that could represent what he saw from a pitching vessel in the midst of a storm. Around the anti-sun of the dark paddle wheel in the center everything else revolves, but not, significantly, in concentric circles. Instead a series of nearly straight lines radiates from the center, including the continuous line made by the mast and the right side of the triangular shadow in the foreground. By making the bent mast participate in a line that is essentially straight, Turner demonstrates his capacity to define and delineate elemental turbulence even while representing its radically destabilizing effect.

In Milton’s Tsunami, which evokes Vernet as well as Turner, the English painter is at once a witness to the storm and the artist at work on a painting, standing with palette and brush in a plein-air studio that has been magically installed on the deck of a three-masted schooner named J.M.W. Turner (left below). On an easel to the left of him is the painting in progress, a composition of breaking waves and floundering boats that looks something like Turner’s 1805 Shipwreck (right below) but is actually Milton’s invention.[14]

J.M.W. Turner, The Shipwreck (1805). Tate Gallery, London

In front of Turner, two palette stools hang slanted in midair, like a pair of dancers forming a V in mid-jump; to the right of him—also easeled-- are The Fighting Temeraire and two more Turners pitched off their easels: The Harbour of Brest: The Quayside and Chateau (reversed) and Rain, Steam, and Speed. But Turner stands securely with feet set apart, and though the sailing craft named for him rides the crest of a giant wave rivalling those of Hokusai (see below),[15] the craft itself is so level that it parallels the horizon.

Katsushika Hokusai, The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Woodblock, ca. 1829-33

Along with the presence of studio furniture and several of Turner’s paintings on the deck, this dead-levelling of the schooner on the crest of a wave exemplifies the kind of liberties that Milton often takes. While meticulously delineating a set of spatially coherent objects, he sometimes frees them from gravity, as he does with the billiard balls floating over the table in Mary’s Turn (left).

Milton also takes considerable liberties with the figure of Turner himself (below left). Though gravitationally steadied with both feet on deck, he bears little resemblance to the bulky, top-hatted figure in long black coat that we typically find in pictures drawn during his lifetime, such as William Parrott’s Turner on Varnishing Day of about 1846 (below right). Besides making Turner much leaner, giving him a low-crowned hat, and stripping him to a shirt and vest, Milton magically fuses the bound, sea-tossed artist—unable to do anything but see the storm around him—with the studio artist freely using his arms and hands to paint. His work-in-progress is not clearly based on what we can see in the rest of the print, but we may well imagine that Milton’s Turner is taking some liberties of his own.

Turning now to the left side of Tsunami, well below the crest of the wave that threatens to overwhelm him, John Constable (far right) gazes calmly back at the schooner while manning the long tiller of a small, foundering sailboat with the words LOYAL ACADEMY wavily fluttering across its sails (near right). Draped like bunting behind the upper part of the jib, the bearded and top-hatted figure of John Ruskin waves a flag stamped RA while stretching out his arms toward Turner. Since Ruskin ardently celebrated Turner’s later work in the five volumes of Modern Painters (1843-60), his gesture may be read as an act of homage as well as an appeal for rescue, though in a moment I will consider a third possibility.

Hovering over the bow of the sailboat--perhaps thrown up by the waves-- are three other Royal Academicians in black top hats, one of whom struggles to get control of the mainsail. And while a fourth man has just tumbled out of the boat beside Constable, he seems to be not so much sinking into the waves as floating on them. All five of Constable’s fellow passengers, in fact, may be construed as somehow capable of flight, or at least of resisting gravity—like the billiard balls of Mary’s Turn.

J.M.W. Turner, The Shipwreck (1805)

Peter Milton, Tsunami (2015)

What does it all mean? We might compare the print to Turner’s Shipwreck (left above), whose relatively shallow trough of foamy waves stretches out between the sinking wreck at left and the gaff-rigged sloop at right; leaning over at about 45 degrees, the sloop may or may not be able to rescue the passengers crowded into the lifeboat heaving in the foreground.But rather than leaning over at all, the schooner named J.M.W. Turner in Milton’s print seems as airborne as the shadowy pelicans gliding low across the waves below it. Defying gravity, its prow shoots straight ahead into thin air. Also, while several shadowy vessels seem to be sinking near the horizon, there is no shipwreck in the foreground, or at least not yet: no sinking vessel, no packed lifeboat. “Tsunami,” Milton writes, “is more about the majesty of nature than the wrecking of ships.”[16] As for Constable’s imperiled sailboat, it remains afloat for now, and his calm demeanor as he mans the tiller with his legs spread easily apart shows not the slightest trace of anxiety. He could be one of Constable’s own boatmen quietly guiding a barge along a canal.

Furthermore, Ruskin’s outstretched arms (left above) not only suggest homage or appeal; they also recall the upraised arms of Turner’s red-robed Ulysses standing in the upper left of his ship (above right), defying the monster that he and his men have just escaped and thus defying also Poseidon, god of the sea as well as father of the monster; though Poseidon later destroys nearly all of the Greeks to avenge their blinding of his son, Ulysses himself survives. Could Ruskin be likewise defying the power of the tsunami? While Milton’s notes on the print describe the sailboat as “disintegrating,” neither of its two chief passengers has yet capitulated to the waves.

J.M.W. Turner, Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory)--The Morning after the Deluge—Moses Writing the Book of Genesis (1843).

In an instant, of course, both of those passengers and their boat may be overwhelmed by the tidal wave, which Milton identifies with Turner himself (online note). Yet since we know very well that Constable’s art was not obliterated by Turner’s, and that it has calmly survived for more than two hundred years, we may speculate that the one-sided contest ostensibly staged by the print is something of a draw. On the one hand, Milton’s Turner reigns supreme, mastering the mightiest waters of the universe in something like the way that the Moses of Turner’s Light and Colour (right) masters -- by the very act of writing about it -- the orb of light that breaks through the vortex of the flood. On the other hand, Constable was never killed by Turner’s gun or Turner’s art. He somehow found a way to steer his boat to calmer waters, or take flight into the radiant realm of his magnificent clouds. To that extent, Constable found his own way of mastering the waters of the universe.

Many thanks to Nicholas Goodman with NineBar Creative for his expert management of the photographs used in this article.

Footnotes

[1] I quote Turner’s will from Martin Butlin and Evelyn Joll, The Paintings of J.M.W. Turner, 2 vols. (Text and Plates). rev. ed. (New Haven 1984): Text p. 96.

[2]Graham Reynolds, Turner, New York 1969, p. 142.

[3]Butlin and Joll, Text, p. 52.

[4]Butlin and Joll, Text, p. 196

[5]Collected Correspondence of J.M.W. Turner, ed. John Gage (Oxford 1980): pp. 86-87.

[6]Farington’s Diary of 8 May 1799, qtd. A.J. Finberg, The Life of J.M.W. Turner, R.A. 2nd ed. rev. by Hilda F. Finberg (Oxford 1961), p. 59.

[7]Andrew Wilton, J.M.W. Turner: His Art and Life (Seacaucus, NJ 1979), p. 87 and p. 105, note 2.

[8]For a survey of Milton’s printmaking up to the year 2000, see James A. W. Heffernan, “Peter Milton’s Turn: An American Printmaker Marks the End of the Millenium,” on this site. On Milton’s recent turn to digital technology see Robert Flynn Johnson, “Some Thoughts on Peter Milton and Digital Printmaking,” also on this site.

[9]Charles Newton, Photography in Printmaking (London, 1979), p. 31.

[10] Email of December 15, 2015 to the author.

[11] Achille Segard, Mary Cassatt: Un Peintre des Enfants et des Meres (1913), quoted in Nancy Mowll Mathews, ed. Cassatt: A Retrospective (China 1996), p. 150.

[12]Butlin and Joll, Text, p. 247. Milton was led to this story by Mike Leigh’s 2014 bio-film Mr. Turner. According to Milton, the print also evokes “my own summer of 1950 working on an oil tanker off the Pacific coast” and “a few of my own pitching and yawing storms.” (Notes on Tsunami of August 5, 2017: https://www.petermilton.com/blog/)

[13]In 1797 Turner copied Claude-Joseph Vernet’s Storm with Shipwreck (1754). I have no evidence that Turner ever saw Horace Vernet’s picture, but since it made a considerable stir at the Paris Salon of 1822, Turner probably heard about it or least about the feat that it depicts. See Butlin and Joll, Text p. 247 and Steven Z. Levine, “Seascapes of the Sublime: Vernet, Monet, and the Oceanic Feeling,” New Literary History 16.2 (1985): 386.

[14]Email of 15 December 2015 to the author.

[15]Since tsunami is the Japanese word for a giant wave typically generated by a seismic event, Milton’s print may well owe something to Hokusai’s woodblock.

[16] Email of 14 December, 2015 to the author.

![J.M.W. Turner, Bridge of Sighs: Ducal Palace and Custom House, Venice: Canaletti [sic] Painting, by J.M.W. Turner. 1833. Oil on canvas 51.1 × 81.6 cm. (Tate Britain, London).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/583c833659cc68a8c3c56675/1516307057328-T8G9OQ2KRZCM3UORNED3/William_Turner%2C_Bridge_of_Sighs%2C_Ducal_Palace_and_Custom-House.jpg)